Artisanal fishermen are one of the most deprived communities in terms of material resources and representation in social standing. The women fisherfolk are the most marginalized among the fisherfolk communities. Open-access fishing leads to the commons’ resource pool crisis or tragedy. Bangladesh has experimented with different community-based fishing models, but most of these models are top-down with the engagement of the local elites, bureaucrats, and local lawmakers. The low political power of the fisherfolks often has drowned their voices. This study surveyed four locations in Kurigram, Sunamganj (Tanguar Haor and Pakna Haor), Chandpur, and Bhola.

Extensive secondary research was conducted regarding the fishing management system in Bangladesh, India, Chile and Philippines (Details in Annex II). Our main finding is that there is a severe governance problem in managing the shared water resource. In the flood plains Jalmahal (water bodies), the elite business has captured and owned the fisherfolk association and disrupted the fairness and transparency of a bidding process. The fisherfolk’s livelihood in the haor areas is dependent on fishing and single-crop agriculture. The communities in the floodplains suffer from extreme poverty and food security because of the restrictions in the fishing by the powerful leaseholder. In the coastal fisheries, the government has imposed a total of 109 days’ ban over a season. The ban period was targeted to allow the healthy spawning of the mother hilsha. But due to laxity in law enforcement and the elites’ ability to carry out extensive fishing using Bhendi net and Moshari net catching large volumes of small hilsha (Jhatka Ilish) during the ban period. The ban has largely failed to increase the fish stocks, instead has resulted in lower yields.

During the ban period, the ordinary fisherfolks experience immense suffering as most fisherfolks’ livelihood depends on fishing and receive only 40 kg of rice per month for the entire family. This social protection package is inadequate for most of the fisherfolk. Moreover, only 50% of the fishermen received the fishermen’s cards. The fisherfolk also regularly face severe harassment and rent collection from law enforcement agencies without any legal recourse.

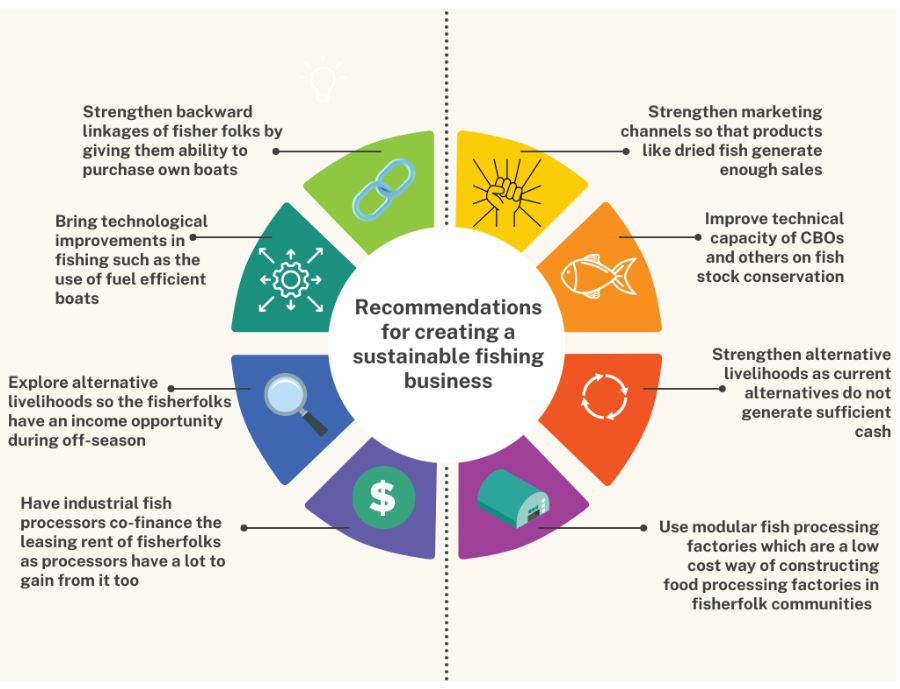

In this sustainable business plan, we have designed a three tier business model and an influencing plan for the government to strengthen the rights of the fisherfolks. The business model is designed within the fishing value chain, including developing entrepreneurship on the upstream market for producing boats and fishing nets. The development of alternative livelihood options is to prevent excessive fishing by a large and growing population of fisherfolks. The alternative livelihood options include the development of business in agriculture, livestock, poultry, pond aquaculture, and pearl culture.

One of the major bottlenecks that the fisherfolk regularly is smoothening their consumption, financing, business operation, and capital needs. The fisherfolks remain trapped in debt because of their high seasonality and vulnerability in income. This study has developed a sustainable financing plan based on the available financial infrastructure, technologies, and products. Finally, an influencing plan has been designed to carry out systematic policy advocacy with the government to ensure accountability of the stakeholders in ensuring the economic, social, and human rights of the fisherfolks. Moreover, this study has reviewed the exploitation of biological resources by the elites in the Jalmohol and the Hilsha ban. A primer on an alternative path towards sustainable fisheries management based on the experience of Philipines, India, and Chile has been proposed.

Write to us at contact@cast-network.com for accessing the full report subject to permission from Center for Natural Resource Studies and Oxfam GB