In Urban parlance, climate change invokes a palpable fear of a depressing future and images of droughts, cyclones and floods. Although for those living in some of the vulnerable coastal areas of Bangladesh, it is not a fear of the future but a living memory of horror and a daily struggle for survival. The local administration in these coastal climate-vulnerable areas is constantly in flux with overwhelming requests for tackling emergencies induced by climate change. In Shyamnagar, the high tide and saline water frequently crack and fracture the road and other vital infrastructures. Dams and culverts do not protect a section of the community in low-lying areas and are often drowned underwater. The salinity in the water causes the most damage as it destroys agricultural lands and seeps into drinking water sources. The fund allocation for social protection does not commensurate with this barrage of loss and damages faced by vulnerable communities. According to a sub-district Government official, “the funding is allocated in areas where salinity is not a big problem”. The Government of Bangladesh has a linear system of allocating social protection, such as vulnerable group development (VGD), based on the population size and the district size. But the most vulnerable communities have sparse populations and limited geographic space.

However, in the sprawling Dhaka city, the Government has inked a deal with Asian Development Bank (ADB) for the Greater Dhaka Sustainable Urban Transport for USD 100 million to build urban road transport infrastructure such as the Rapid Bus Transit from Gazipur to Dhaka. This massive infrastructure investment for road connectivity is earmarked under climate financing. According to the Finance Division, Bangladesh has spent over USD 3 Billion in climate financing in the fiscal year 2021-2022. The characteristics of the projects considered under climate financing are mostly related to infrastructure development and most of these infrastructures need to be designed according to the needs of the local communities. According to community members in Nilphamari (Dimla Upazila), Sathkhira (Shyamnagar Upazila), and Barguna (Barguna Sadar), the infrastructures that are constructed are designed without considering the local contexts.

During the full moons of July and August 2022, hundreds of villages were inundated twice daily for at least a week per round in the coastal Barguna district. It brought about economic and non-economic losses and damages with both short- and long-term consequences.[1]The local communities have voiced that the mud embankments that have been developed by the Bangladesh Water Development Board (BWDB) have often failed to stop the inundation, as the dams were not designed in consultation with the locality, the height of the embankments did not commensurate with the height of the high tide. Moreover, the design of the roads and embankments often needs to be fixed. In addition, the local leaders in the community alleged that the contracting process of the work assigned from BWDB changes hands many times, leading to faulty constructions and less accountability for the contracts.

Oxfam in Bangladesh and the Center for Natural Resource Studies (CNRS) recently conducted a study on reflection on the National Adaption Plan on National and Local Budget, and their finding is that there is a strong disconnect between the demands of climate-vulnerable populations from the grassroots regarding building climate resilience and the climate financing that are allocated. The Government of Bangladesh has recently approved the National Adaptation Plan (NAP) 2022. It is a comprehensive document for the core planning and investment document to adapt to climate change over the next 28 years. NAP has an ambitious budget of USD 230 billion over the next 28 years, with an annual financial outlay of USD 8.21 billion per year. However, this extraordinarily ambitious budget has no specific strategic financial sourcing guidelines. But more importantly, NAP has yet to be formulated without considering a local adaptation plan of action (LAPA). LAPA is crucial in identifying the mechanism through which local communities can adapt using local resources. NAP also did not consider the community-led regional vulnerability assessment in constructing interventions that consider the local vulnerabilities within a district and across the countries.

Although the National Adaption Plan of Bangladesh has undergone a comprehensive consultation process, the study from Oxfam and CNRS has revealed that most of the local government actors and members of the union disaster management committees from the most vulnerable areas have not been consulted in the process of developing the NAP. The consultative approach was lean at the union level, where the vulnerability is much more pronounced. Another major drawback of the NAP is that it has no legislative bindings and meanigful accountability mechanism. There are 113 planned interventions that need a concrete roadmap of the implemeentation with clear indication of the source of funds and institutional responsibility to implement the planned interventions.

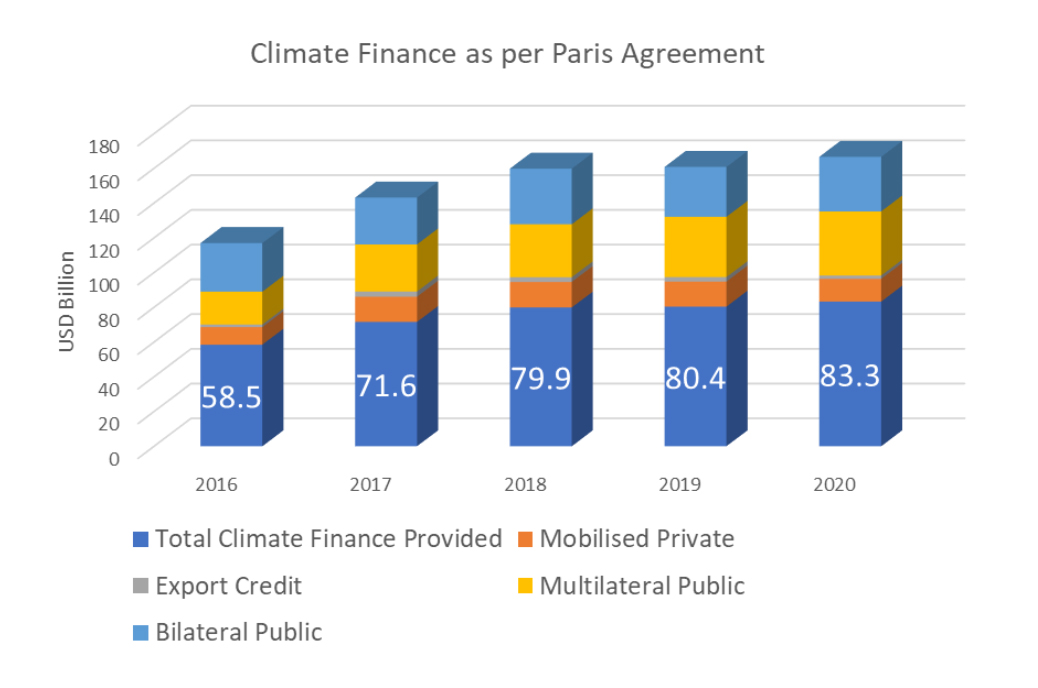

Global climate funds such as Green Climate Fund (GCF) and Private Sector funding have been quoted as the possible accelerated funding source for operationalizing NAP, but if we look at the disbursement of the Global Climate Fund, the picture is quite dreary. The chart below shows climate finance disbursed by the developed country as per USD 100 Billion commitment per annum from the developed country. Not only did the developed countries keep their commitment to meeting the climate financing goals, but about 50% of the funding was also provided through loans and about 70% of the funds were utilized in mitigation for developed countries. Moreover, since its inception GCF has only disbursed USD 374 million in climate financing to Bangladesh against a requirement of at least USD 1 Billion per year. The climate emergencies faced by Bangladesh do not have any space for such a lengthy financing process. Fundamental reforms are required in Bangladesh’s climate policy discourse to ensure that the allocation, utilization, efficiency and possible pool financing are systematically designed.

OECD 2022 has published a report reflecting on the commitments of the Paris Agreement, the table above shows that the developed countries have not kept the commitment of disbursing USD 100 per year, and the climate finance provided and mobilized by developed countries largely focused on mitigation in relative high emitting countries and the anticipated mobilization by the private sector was very low.

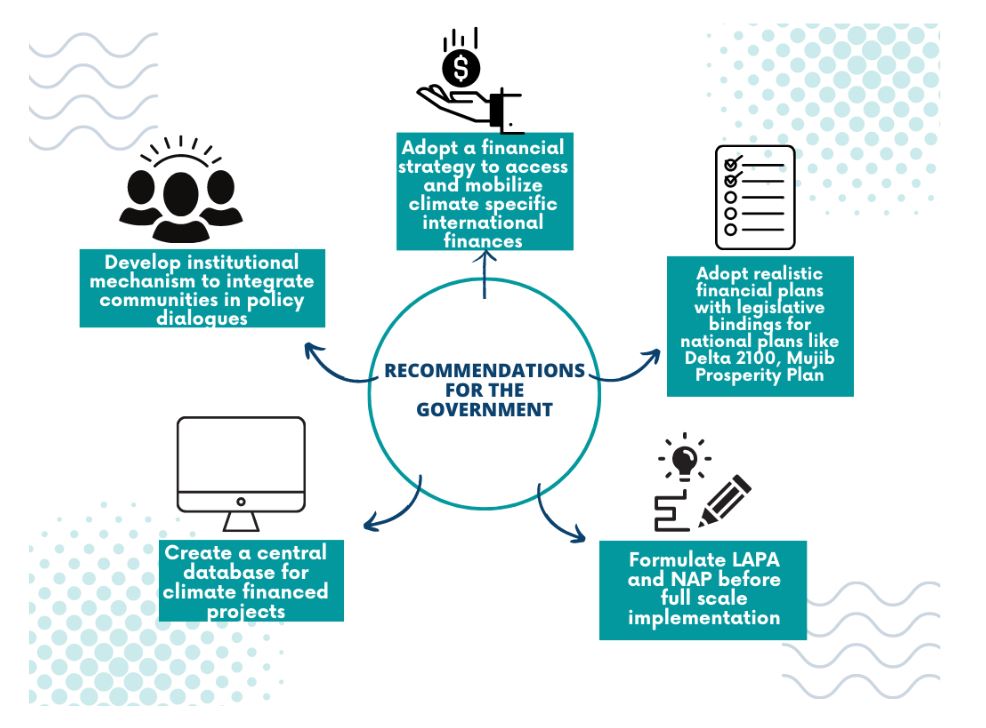

In light of the local and global climate policy landscape, the Government of Bangladesh can consider the following recommendation.

- The Government of Bangladesh needs to urgently adopt a financial strategy to access as well as mobilize climate-specific international and national finance to implement its climate plans.

- The costed plan such as the Mujib Prosperity Plan, the Delta Plan 2100 and NAP needs to be augmented with a realistic financing plan with legislative binding of financing and monitoring of the quality of the projects.

- The Government also needs to formulate the LAPA and accordingly adapt the NAP 2022 before going on full-scale implementation of the 113 interventions.

- There needs to be a central database for climate-financed projects. The different Ministries and departments can collaborate and coordinate more effectively if there are more data available in the public domain regarding the projects.

- Finally, the institutional mechanism for integrating communities in core policy influence and diversified fundraising needs to be developed. The baseline survey findings and community perceptions need to be taken as a mandatory criterion before the implementation of projects. The ownership of the local communities through token collections and central CSR and Zakat fund can ensure financial sustainability and the community’s right.